I am not a videographer and generally won't highlight a lot of such videos, but what Chris Bryan was able to capture here is simply stunning. Be sure to view full-screen and in 1080p HD. (The nice Hans Zimmer soundtrack doesn't kick in until around 1:40.) All footage was shot using the Phantom Flex, Phantom Miro M-320S and the new Phantom 4K Flex with Arri Ultra prime lenses.

100 Year-old Panoramas of New York

Library of Congress

Retronaut presents a collection of 12 widescreen images of New York City that date back to the end of the 19th century and which are sourced from the Library of Congress' collection of panoramic photographs. Having photographs dating back a century or more is one thing, but to have a collection of panoramas from this era is quite another.

Great Art History Video

MoMA presents a brief art history video.

“A Priori”

One of my favorite observations pertaining to the vast realm that is art was made by Paul Gauguin: “Art requires philosophy, just as philosophy requires art. Otherwise, what would become of beauty?”

When I was graduate student at Virginia Tech I had the opportunity to participate in a form of an “educational exchange” wherein I partook of a semester-long graduate course in philosophy through Harvard University’s Extension School. The subject of the course was metaphysics.

If you reference any reputable guide to metaphysics, you will quickly find that metaphysics — especially today — is difficult to define. In fact, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy declares (in the very first sentence of its somewhat broad online treatise), “It is not easy to say what metaphysics is.” A few quick paragraphs later we find another not so helpful statement: “The word ‘metaphysics’ is notoriously hard to define.”

Great, thanks for clearing that up.

In fact, there is even considerable disagreement today amongst philosophers not only with regard to exactly how metaphysics is to be defined but also with respect to which sub-branches of philosophy are to be included within its nexus.

(Imagine that — disagreement amongst philosophers!)

Nevertheless, to present the briefest summary possible — although this summary would surely broach a diligent and comprehensive conversation by those who may disagree — the study of metaphysics represents an exploration of “first causes.” By “first causes” we are speaking of existence itself (including matter) and the resulting causes of such existence. Additionally, and by extension, we are also speaking of the study of the nature of existence itself — not only the “stuff” of existence but the intangible nature of reality as well.

By the way, philosophers beginning with Aristotle (who is considered the father of metaphysics) all the way to the 21st century have included the idea of God as the origin of all existence (along with defining its nature) down to the more traditional theoretical antecedent of the Big Bang.

What this means — and this could constitute a more precise definition — is that metaphysics represents “the philosophical study of being and knowing.”

If you believe this is all getting a little thick by this point, just bear with me.

What is existence? If we exist, what makes up the constituent nature of such an existence? And furthermore, how do we know? How do we know we know? How do we know anything, really?

These questions are all found within the comprehensive umbrella of metaphysics. (Although some would say that we have now broached the subject of “ontology” and “epistemology.” But that is for another time.)

… And the point, Kevin?

Within this semester-long smorgasbord of philosophical delicacies, our excellent professor focused on one particular metaphysical morsel above all others. It signified to him the summum bonum of not just the study of metaphysics but of the study of philosophy itself: a priori.

(The phrase is pronounced ah pree-awr-ee or ey pree-awr-ee, depending upon your philosophical perspective).

Great, Kevin! Just great. Yet another philosophical morass.

Not so!

The concept of a priori is, to me, one of the more savory aspects of metaphysical inquiry because it is at once more easily defined and at the same time more mysterious than general metaphysics. It was this mysteriousness that captivated our professor.

And don’t worry, we’re coming close to the end of today’s mini-thesis.

For the purposes of not only this blog post on my color abstract photography work — yes, I haven’t forgotten about that — but also as a summary of our professor’s teachings on the subject, a priori simply means “the awareness and/or comprehension of reality (of existence, if you will) which is independent of personal experience.” It is this independence from personal experience which forms the key to the mysterious nature of a priori.

In other words, the term refers to that knowledge which is independent of any “first-person” experience one has enjoyed throughout their sentient lifespan. And we are not necessarily speaking of a “sixth sense” here, although a “sixth sense” may (or may not) be indicative of a priori awareness. (A “sixth sense” may simply represent an as yet defined awareness which is the product of rational experience and its attendant comprehension.)

In its most unpretentious form, a priori can mean the simple “awareness” that all bachelors are unmarried men. In other words, it does not require that the individual possess a first-hand, first-person knowledge — by literally coming in contact with all adult males who are not married — in order to possess a logical understanding of a portion of humankind’s sociological makeup.

Another example would be the specific mechanics associated with the earth’s rotation around the sun. None of us has sufficient first-hand, first-person experience to be able to declare that we know matter-of-factly and can attest to the reality of this precise gravitational relationship. Instead, we rely upon the testimonies of others (such as physicists and astronomers), along with the predictions associated with mathematics, to find comfortability in such a reality.

Yet according to my former Harvard professor, a priori also extends to those realms of awareness beyond reliance upon common assumptions, if you will, or the testimony of authority figures. A priori seems to extend to those aspects of awareness which one might term as “innate.”

The uptake of all of this means that on many levels a priori contradicts one of the foundations of epistemology (that branch of philosophy that investigates the origin, nature, methods, and limits of human knowledge) in the form of the 18th century English philosopher John Locke’s declaration that “no man’s knowledge can go beyond his experience.” In other words, according to Locke you can only truly know what you have personally experienced. If you have simply read about a concept, construct, idea, place, time, object, etc., but have never experienced such in the first-person — through the physical senses — then you do not truly possess knowledge of the same.

So far so good.

But now here’s the rub: a priori justification (as it is now called) constitutes a well respected phenomenon within the larger realm of epistemology and metaphysics.

OK… Go on…

But if the individual possesses a true comprehension (a true awareness) of that which did not result as a product of the utilization of the five human senses — through personal sensory experience — how exactly did the individual acquire such “knowledge”?

That is the question that fascinated our professor. Furthermore, the more he was able to show the reality of “deeper” examples of a priori — by metaphysical experiment and logic — the more we all began to question and appreciate such supposedly innate knowledge.

Once again, are we referring to a sixth sense? Are we speaking of the acquisition of certain traits (or “talents”) acquired through the genetic-mutation process that is human procreation? Or are we speaking of something else when we refer to the ultimate workings of the a priori principle? According to my former Harvard professor, genetic mutations alone cannot explain all that seems inherently innate.

The concept of a priori has been analogized to intuition. In fact, there are a number of published papers within the philosophical realms that seek to compare and contrast intuition with a priori (the formal definition for intuition being “an immediate cognition of an object not inferred or determined by a previous cognition of the same object.”) The point being, we are speaking of what is also referred to in these same philosophical realms as "special knowledge." And once again, the question is: how is such special knowledge obtained?

My goal in creating a priori as a piece of abstract fine art was to represent that knowledge that is, at least seemingly, independent of sensory awareness.

Thus, what is the origin of such knowledge…?

This work constitutes the artistic representation of my answer to this question.

Paris Past & Present

Julien Knez

Photographer Julien Knez combines his World War II era photographs with ones of today. Remarkable.

April Fool's Photo-editing Tip

Love this...

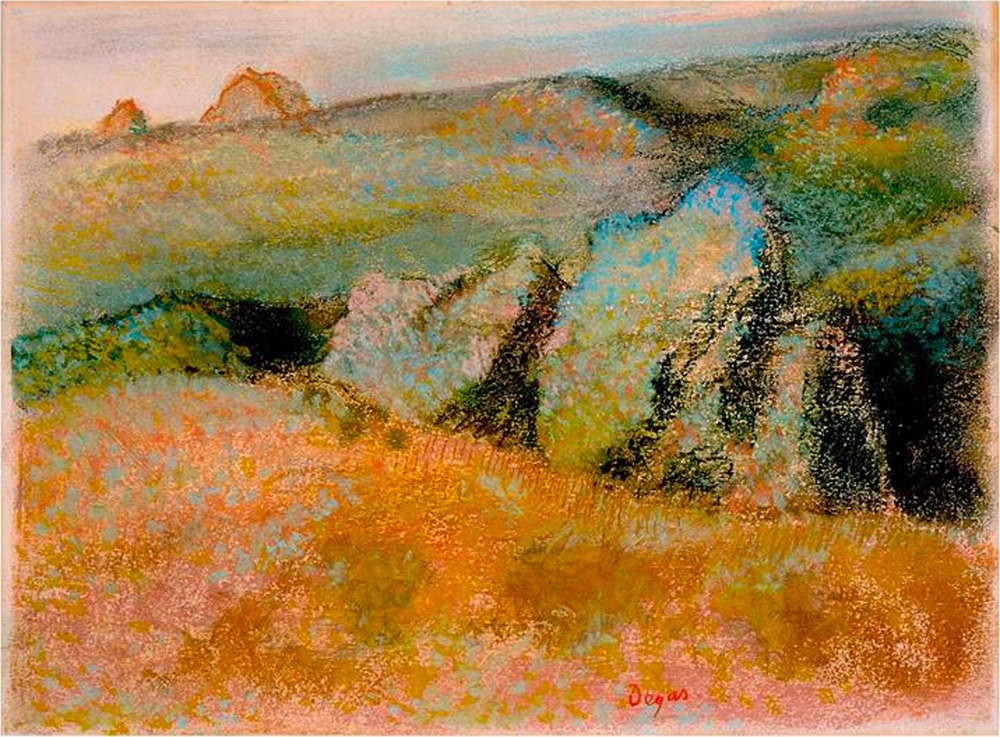

Edgar Degas as Early Experimental Photographer and Printmaker

National Gallery of Art

The Wall Street Journal reports today something of which I was unfamiliar: that Edgar Degas was "an early enthusiast of photography — guests complained of being forced to pose after dinner," and that further "he employed the new medium, at least occasionally, as the basis for his art."

Degas was surely one of the most passionate artists of his time. "As a sculptor, he disregarded conventional methods... As a collector, he acquired, among countless other works, everything he could by the Neoclassicist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, drawings and watercolors by the Romantic Eugène Delacroix, and innumerable drawings by the realist illustrator Honoré Daumier, as well as one of the few canvases sold from Paul Gauguin’s exhibition of works from his first sojourn in Tahiti."

Degas also experimented with monotypes "[occupying] a strange territory between painting and printmaking... Powerful as Degas’s monotypes of figures are, the most surprising works... may be the landscapes. Made in the early 1890s, and sometimes based on shadowy second pullings, they are unusual for using color and astonishing for their economy and directness."

High Gallery of Art

1930s "Killed" Photographs

Library of Congress

Mashable reports, "The photos look just like the most famous... images of Depression-era America. Laborers with weathered faces stare into the distance, sharecropping families stand on splintered porches and rag-clad children play in the dust. But each picture is haunted by a strange black void. It hangs in the sky like an inverted sun, it eclipses a child’s face, it hovers menacingly in the corner of a room. The black hole is the handiwork of Roy Stryker, the director of the Farm Security Administration's (FSA) documentary photography program. He was responsible for hiring photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein and Gordon Parks and dispatching them across the country to document the struggles of the rural poor."

"When the photographers returned with their negatives, Stryker or his assistants would edit them ruthlessly. If a photo was not to his liking, he would not simply set it aside — he would puncture the negative with a hole puncher, 'killing' it."

Photographer Edwin Rosskam declared, "[The] punching of holes through negatives was barbaric to me... I’m sure that some very significant pictures have in that way been killed off, because there is no way of telling, no way, what photograph would come alive when."

Beyond tragic...

Yesterday's GoPro

This image is from 1960. And yes, that's a functioning video camera attached to that man's helmit.

As you can see from this photo, because of its weight it was most probably and literally a pain in the neck.

Furthermore, the video resolution was far inferior to the 4K resolution of today.

To see how far we've come click here.

“Serotonin”

It must be stated upfront that I have absolutely no formal training in biochemistry or neurochemistry whatsoever. This should come as no surprise to those who have any knowledge of my educational background. My training is in the political sciences. Nevertheless, I have long been fascinated by a molecule that was originally discovered in 1948: serotonin.

One of the most comprehensive overviews of serotonin can be found in a 2011 New York Times article. Here is one of the juicier portions of that article:

“For all the intricacy, serotonin in the brain has a basic personality. ‘It’s a molecule involved in helping people cope with adversity, to not lose it, to keep going and try to sort everything out,’ said Philip J. Cowen, a serotonin expert at Oxford University and the Medical Research Council. In the fine phrase of his Manchester University colleague Bill Deakin, ‘it’s the ‘Don’t panic yet’ neurotransmitter,’ said Dr. Cowen. Given serotonin’s job description, disturbances in the system can contribute to depression, anxiety, panic attacks and mental calcification, an inability to see the world anew…”

A link to this fantastic article can be found here.

The latest research suggests that this molecule has neurotransmitter, hormonal, and tissue-building properties all in one. In fact, scientists have recently noted that serotonin is implicated in the construction of nerve tissues themselves.

Furthermore, we’ve all become at least somewhat aware of the bounteous supply of pharmaceuticals — both legal and not so much — which seek to enhance serotonin’s unique properties in the bloodstream and particularly its effect upon the brain.

In short, it may be said that serotonin represents — in the most comprehensive and intricate of fashions imaginable — the essential “just chill” biochemical particle. It is both wonderfully simple and yet at the exact same time extraordinarily powerful in its constitution and in its effect.

More to the artistic point, serotonin has a profound effect on how we see the world and its constituent parts — literally.

Given this very brief background on the molecule that is serotonin, some may already begin to see a connection between its properties and the essential nature of this color abstract photography work. However, I must highlight the fact that I did not intend to create a work symbolizing serotonin’s effect upon human consciousness.

Rather, and as I have already noted in a prior post, when it comes to my color abstract photography work, “I begin with an idea and then it becomes something else.” (Pablo Picasso) It is as veritably true with “Serotonin” as with any of my other works.

Over the many months of intensely focusing upon “Serotonin” and then leaving the work alone for a period of time — repeating this pattern over and over again — I began to gain a sense of not only how I was impacting the work but how the work was impacting me (something which happens with each and every piece of fine art I am fortunate enough to create).

Therefore, and if it may be possible for me to note, I began to notice more keenly serotonin’s actual biochemical/neurochemical effect upon me the more I sought to evoke serotonin’s presence in the color abstract work itself.

It’s been a wonderful time of discovery.